Part One

The smell of pine hung in the December air, sharp and clean against the diesel fumes of US-1. It was the early 1990s, a few weeks before Christmas, and the lot outside a shopping center in Homestead, Florida, was busy with families. Children tugged at their parents' sleeves, pointing at the tall Fraser firs. Somewhere, a radio played "Silver Bells." The trees stood in neat rows, their branches still bound with twine, price tags fluttering in the warm breeze.

Glenn Walker was checking inventory near the back of the lot when two men walked in. They didn't browse. They didn't look at trees. They walked through the rows, past the families, past the children, past the couple still debating their purchase, and stopped in front of Glenn.

You could tell they weren't interested in buying Christmas trees. You could tell they had guns.

What happened next would stay with Glenn for the rest of his life. He ran. The men followed. They raised their weapons and fired. The bullets missed. Glenn kept running, weaving through the lot, through the trees, knocking over a display of wreaths. He burst onto US-1, the six-lane highway that runs down Florida's eastern coast, and tried to flag down a car. No one stopped. The traffic kept moving, drivers staring straight ahead, unwilling to get involved. Glenn stood in the middle of the highway, waving his arms, and still no one stopped.

Finally, he jumped onto the hood of a moving car. The driver had no choice but to brake. Glenn scrambled off, and the men, seeing the commotion, the witnesses, the chaos they had created, disappeared.

The police came. Glenn gave his statement. Families who had witnessed the chaos gave theirs. And then, because he was Glenn Walker, he went back to work. He hired an armed guard for the lot, a man with a shotgun who would stay with him through the rest of the season. There were trees to sell. Christmas was coming.

He never found out who sent the men. But he didn't stop selling Christmas trees. He didn't leave Florida. He hired an armed guard and finished the season. The only thing he changed was his expectation of what his enemies might do.

If anyone ever came for him again, he figured, they would rough him up. Break some bones. Send a message with fists instead of bullets.

He was wrong about that.

Glenn Walker was not a man who backed down. This was something you understood about him within minutes of meeting him, and it was something that had been true his entire life.

He came from Jefferson County, Florida, a rural community in the northern part of the state where his family had farmed for generations. The Walkers were a large clan, one of those sprawling Southern families where everyone knew everyone and a man's reputation was the only currency that mattered. Glenn's father was one of twelve children. His grandfather was one of thirteen. When you started counting cousins, aunts, and uncles, the numbers ran into the dozens. They all lived within a few miles of each other, worked the same land their ancestors had worked, attended the same churches, and married into the same neighboring families.

"Their handshake was their word," his wife Donna would say later. "They would pay people to do things, but they would not pay people not to do something."

It was a distinction that might seem subtle to an outsider, but it meant everything to the Walkers.

Donna remembered a time when she was practicing law and represented one of Glenn's cousins, a man who owned a fertilizer business. A customer had refused to pay, and they took him to court. After the trial, the cousin turned to Donna, bewildered. "He lied on the stand," the cousin said. "He did not tell the truth." To the Walkers, this was incomprehensible. If the man had told the truth, they wouldn't have needed to go to court in the first place. A deal was a deal. Your word was your bond. Lying was simply not something you did.

Glenn's mother came from the Jones family, and the Joneses had a different kind of reputation. During Prohibition, they had been bootleggers, running illegal liquor through the piney back roads of North Florida. The region was a hotbed for moonshining in those years, with local sheriffs often looking the other way as stills bubbled in the woods and unmarked trucks ran loads through the night. The Joneses were among those bold folks willing to operate outside the law when the law didn't make sense to them. Glenn had inherited something from both sides of his family: the Walker stubbornness and the Jones appetite for risk.

He was the first in his family to leave Jefferson County in any meaningful way. Most of his cousins stayed close to home, married local, took over their fathers' farms, or found work in nearby Tallahassee. Glenn went to Florida State University, where he met Donna in a geography class in 1967. She had actually noticed him before that, in a freshman biology lecture, where he sat in the front row and slept through most of the class. Her girlfriend had pointed him out. But they didn't speak until the following year, when he asked her out.

Their first date was at a Big Boy restaurant. Glenn ordered dinner, and when they finished, he asked if she wanted dessert. She said yes. She loved their strawberry pie. When the check came, he paid it and left a fifty-cent tip. Donna, who had spent her summers working as a waitress, quietly added several dollars to the table after he got up. She found out later that the dinner had cost him everything he had. He had spent his last money taking her out, and he hadn't said a word about it.

They dated for thirteen years before getting married. In that time, they went to law school together at DePaul University in Chicago, working their way through by buying run-down buildings, renovating them with their own hands, and selling them at a profit. Glenn could do most of the work himself – everything except plumbing and electrical. They lived on the second floor of one building while renting out the first. They scraped paint and installed drywall by night, attended classes by day. Their last building was a three-story building on Kenmore Avenue that they converted into condos and sold for a sixty-thousand-dollar profit when they graduated.

After law school, they bought a Volkswagen Kombi camper van and spent six months driving across Europe and North Africa. Starting in Amsterdam, they motored through Western Europe, crossed into Morocco, continued east through Algeria and Tunisia. They wanted to keep going to Egypt, but the region was at war. So they looped back, ferrying to Sicily, driving up through Italy, across into Yugoslavia and Turkey, and even into Iran, where the Shah still ruled, and Americans were still welcome.

Glenn was the one who made things happen, who talked their way through border crossings, who fixed the van when it broke down in the middle of nowhere. "I would never have done it without him," Donna said. This was the man who would later refuse to pay protection money to the mob: someone who had talked his way across three continents in a Volkswagen, who had never met a problem he couldn't solve through stubbornness and charm.

They did it again a year later: six months driving from Florida to Panama, then flying to Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Glenn Walker, the country boy from Jefferson County who had never met a Jewish person until he went to college, had seen more of the world than anyone in his family ever had.

When they returned to Florida, Glenn tried practicing law. He didn't like it. He was restless, entrepreneurial, always looking for the next opportunity. His cousin Charlie Walker was a watermelon broker, and one summer Charlie had a problem: a truckload of melons had been rejected in New York, and he needed someone to go up there and salvage the situation.

Glenn went. And he saw something.

The Hunts Point Market in the South Bronx was one of the largest wholesale produce markets in the world. It covered forty acres of warehouses, loading docks, and refrigerated storage facilities along the East River, a sprawling complex that had been built in the 1960s to consolidate the city's scattered wholesale markets into one location. Thousands of workers moved through it every night, unloading trucks that arrived from farms across the country and around the world. The market fed New York City: its restaurants, its grocery stores, its corner bodegas, its street vendors. Every piece of fruit, every vegetable, every cut flower that New Yorkers consumed passed through Hunts Point at some point in its journey from farm to table.

The market came alive after midnight. By one in the morning, the place was chaos incarnate: forklifts beeped and weaved among semis and piles of crates, vendors and buyers haggled loudly in English and Spanish and Korean and a dozen other languages, and the air was a heady mix of rotting lettuce, diesel exhaust, overripe fruit, fresh herbs, and the coffee that poured from all-night diners where exhausted workers grabbed a few minutes of rest. Peak activity ran between midnight and six in the morning, when fresh shipments arrived, and buying happened. Deals were made with handshakes, payments in cash, and relationships built over years of repeated transactions.

It was a world unto itself, with its own hierarchy and its own code. And it was controlled by the mob. The system operated on a philosophy of managed competition: "Today is your day, you get yours. Tomorrow is my day, I get mine. But everybody gets theirs if we all just sort of keep everything the same." Same pricing. Same territories. Same understanding of who got what and when. An all-cash market was a good place to launder money. The families who ran it had been running it for decades.

Glenn learned the rhythms. He started buying watermelons from farms across the South, following the harvest as it moved north through the season. South Florida in the spring, when the first melons came ripe. Georgia and the Carolinas in the summer. Delaware by late August. He would buy the melons at the farm gate, arrange trucking to New York, and sell them to retailers at Hunts Point. He specialized in a particular kind of watermelon – smaller, dark green, real red inside – that he sold to the Korean corner markets, the delis, the shops that sliced them and sold pieces to customers on the go. The margins were thin, the work was hard, and the hours were brutal. But Glenn was good at it.

At Hunts Point, Glenn got to know the other produce men. There was Frankie, who had been working the market for years and dealt in the same seasonal goods. Glenn and Frankie were friendly at first. They were in the same business, working the same hours, navigating the same system. Frankie had connections that Glenn didn't, relationships that went back decades, ties to people who could make problems appear or disappear. Glenn didn't ask too many questions about those connections. In the beginning, it didn't matter.

It was a friend back in Jefferson County who first mentioned Christmas trees. The friend grew Fraser firs on his land, and he told Glenn there might be an opportunity in New York. The city consumed millions of trees every December, and the margins were better than watermelons if you could secure the right location.

To understand what Glenn Walker was getting into, you have to understand the Christmas tree business in New York. And to understand that, you have to understand a man named Joseph Armone.

Armone was born in 1917 on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the child of Italian immigrants who had come to America in the great wave of migration at the turn of the century. The neighborhood was a cauldron in those years – tenements stacked five and six stories high, pushcart vendors choking the streets, a dozen languages shouted from windows, and underneath it all, the nascent structures of organized crime taking root in the chaos. The Italian gangs were consolidating, carving up territories, establishing the hierarchies that would eventually become the Five Families. Young men with few prospects and considerable ambition looked at the legitimate economy – the factories, the docks, the sweatshops – and saw a ceiling. They looked at the gangs and saw a ladder.

Armone climbed. By his early twenties he had attached himself to the Gambino organization, working his way up through the lower rungs: running numbers, collecting debts, proving himself reliable in the small assignments that tested whether a young man had the temperament for larger ones. He was not flashy. He was not violent by reputation, though he was certainly capable of violence when the situation required it. What distinguished Armone was his eye for opportunity – his ability to look at a legitimate business and see the angles, the pressure points, the places where a wise guy could insert himself and extract value without killing the enterprise entirely.

The Christmas tree trade was one of those opportunities.

It started, as near as anyone can reconstruct, in the depths of the Depression. The economy had collapsed, millions were out of work, and yet every December, New Yorkers still wanted Christmas trees. It was one of those small pleasures that people clung to even in hard times – the smell of pine in a cramped apartment, the ritual of decorating, the brief illusion of abundance in a season of scarcity. The trees came down from Vermont and New Hampshire on trucks, sold by vendors who set up on street corners and vacant lots, and the business was almost entirely unregulated. No licenses to speak of, no oversight, just men with trees and customers with cash.

So Armone provided them with protection. For a fee.

The system was elegant in its simplicity. A vendor who paid tribute – a few hundred dollars at first, though the amounts would rise over the decades – could operate without interference. His trees wouldn't be stolen. His lot wouldn't be vandalized. His workers wouldn't be threatened. He was, in the parlance of the trade, "with" the organization, and that affiliation bought him peace. A vendor who refused to pay discovered what interference meant: slashed trees, broken equipment, fires in the night, visits from men who made clear that the problems would continue until the tribute was paid.

The message spread quickly. Within a few seasons, nearly every significant Christmas tree operation in New York was paying. The amounts were not ruinous – a few hundred dollars, later a few thousand, were manageable for a business that might gross tens of thousands in a good December. Many vendors didn't even think of it as extortion. It was simply the cost of doing business, like rent or insurance or the bribes you paid to building inspectors. You factored it into your prices, passed it along to your customers, and moved on.

Armone earned the nickname "Piney" for his involvement in the Christmas tree racket, a name that stuck with him for the rest of his life. It was an almost affectionate moniker, the kind of thing the newspapers loved – the gangster with the holiday hustle, the mobster who'd cornered the market on Christmas cheer. But there was nothing affectionate about the system he had built. It was extortion, pure and simple, enforced by the threat and occasional reality of violence. And it worked.

Armone rose through the Gambino ranks over the following decades. He went to prison in 1965 on a tax evasion charge – the same crime that had brought down Al Capone a generation earlier – and served nearly a decade. He got out, resumed his position, and kept climbing. By the 1970s, he was a capo, a captain with his own crew and his own territory. By the 1980s, he was underboss, the second-most-powerful figure in the entire Gambino organization, answering only to Paul Castellano and later to John Gotti himself.

Through it all, the Christmas tree tribute system continued. It had become institutionalized, passed down through the organization like any other profitable enterprise. The specific collectors changed, the territories shifted as various crews rose and fell, but the fundamental structure remained intact. Every December, the vendors paid. Every December, the money flowed upward. It was one of dozens of similar rackets that the families operated – tribute systems embedded in fish markets and garbage hauling, in construction and trucking, in any industry where small operators were vulnerable, and cash changed hands in volume.

By the time Armone died in 1992 – he passed away in a federal prison medical facility, still serving time on racketeering charges – the Christmas tree shakedown he had pioneered was more than sixty years old. Three generations of vendors had paid into the system. Fathers had passed the obligation to sons. The tribute had become as much a part of the Christmas tree business in New York as the trees themselves.

Nobody had successfully defied it in all that time.

By the 1990s, the practice had spread beyond the original Gambino operation. In the Bronx, a Genovese family capo named Angelo Prisco controlled the northeast section, collecting payments from anyone who wanted to sell trees in his territory. The system was remarkably stable. It survived changes in leadership, federal prosecutions, the rise and fall of various crime families. It survived because it was profitable and because most vendors accepted it as a cost of doing business. A few hundred or a few thousand dollars a season was a small price to pay for the right to operate without interference. Most vendors didn't even think of it as extortion. It was just how things worked.

The tree men themselves were characters, colorful and competitive. They called themselves, half-jokingly, the "five families of Christmas" – a handful of dynasties that dominated the New York trade. There was Scott Lechner, who wore a fedora and operated out of a trailer in SoHo, who had been paying tribute since the early eighties and considered it simply the cost of doing business. There were families in Brooklyn who had passed their lots down through generations. There were operators in Manhattan who controlled entire neighborhoods, their territories as clearly defined as any mob boss's turf.

These tree men were frenemies, as one of them put it. They would buy you a drink and then try to steal your customers the next morning. They fought over corners, over suppliers, over prices. They spread rumors about each other's trees, sabotaged each other's displays, and poached each other's workers. But they all paid their tribute. That was the one thing they had in common.

Glenn Walker did not see it that way.

Glenn was not sentimental about Christmas trees. He didn't have childhood memories of decorating firs with his family or any particular attachment to the holiday. What he saw was a business opportunity: a seasonal product with high demand, a compressed selling window, and the potential for significant profit if you executed well.

He started investigating. He drove to Pennsylvania and met with growers, spending days walking through tree farms, learning the business from the ground up. Pennsylvania had more Christmas tree farms than any other state in the country – over 2,100 operations scattered across the Poconos and the rolling hills of the central part of the state. The farms ranged from small family plots to sprawling thousand-acre operations where helicopters lifted bundles of cut trees from the fields to waiting trucks on the roads below.

Glenn walked the rows with growers, learning to read the trees. Fraser firs from the mountains of North Carolina, with their silver-green needles and strong branches, were the premium product, the trees that wealthy customers wanted in their living rooms. They wholesaled for twenty dollars or more for an eight-footer. Balsam firs from Vermont and Maine had a stronger scent but softer branches. Douglas firs were popular but expensive to ship from the Pacific Northwest. Scotch pines were the workhorses – hardy, affordable, maybe five dollars wholesale for a decent specimen. White pines were at the bottom of the barrel, sold to customers who couldn't afford anything better.

He learned about shearing, the annual trimming that gave trees their perfect conical shape. He learned about grading – premium, number one, number two – and how the grade determined the price. He learned about the harvest: crews moving through the fields in October and November, cutting trees with chainsaws, binding them in mesh netting, loading them onto trucks for the journey to the cities. He learned that timing was everything. A tree that sat too long in a hot truck would drop its needles within days of being put up in someone's home.

Each fall, Glenn would drive out to Pennsylvania, walk the fields, and tag the trees he wanted with colored ribbon or spray paint. By mid-November, flatbed trucks would arrive at the farms, workers would cut their tagged trees, and the loads would head south to the Bronx.

Glenn secured a lot on Bartow Avenue in the Baychester section of the Bronx, near the Bay Plaza Shopping Center. It was prime real estate: across from a Toys "R" Us, just down the road from the entrance ramp to I-95, and within sight of Co-op City – the massive housing complex that dominated the skyline of the northeast Bronx. Co-op City was a city within a city, thirty-five high-rise apartment towers between twenty-four and thirty-three stories each, home to tens of thousands of families. They all needed Christmas trees.

During December, Glenn's rented lot transformed into a miniature forest. Rows of fresh-cut Fraser firs, balsams, Scotch pines, and Douglas firs stood on display, their branches still bound with twine, price tags fluttering in the cold wind. Wooden shacks painted red and green served as warming stations and checkout areas. At night, string lights created a warm glow visible from the intersection, and the smell of pine resin mixed with the exhaust fumes from the Bartow Avenue traffic. Customers could pull off the busy road, park, and wander through the trees the way you might wander through a forest, looking for the perfect one.

Glenn divided the lot into two sections: one for budget trees at fourteen dollars and ninety-nine cents, one for premium trees at higher prices. A hand-painted sign near the entrance announced it: ANY TREE $14.99. The budget section was a draw, bringing in customers who often ended up buying something more expensive once they saw the quality of the Fraser firs.

The $14.99 price point would prove to be a problem.

Word got out all over the city. There's a guy up in the Bronx selling any tree for $14.99. Vendors down at Amsterdam Avenue and 90th Street, selling their trees for forty-five or fifty dollars, started hearing about it from their customers. "Why should I pay you fifty bucks when there's a guy in the Bronx selling them for fifteen?" It was disrupting the market, undercutting the established players, threatening the careful equilibrium that kept everyone profitable.

Glenn didn't care. This was capitalism. This was America. He could sell his trees for whatever he wanted.

Donna stayed in Florida during the school year, raising their son, Glenn III – "Rascalhead," as his father called him. But after school let out for the holidays, she and the boy would drive up to New York and help with the lot. She handled the money, kept the books, and reconciled the accounts. Glenn's record-keeping was like most farmers she knew: the dashboard of his truck was his filing cabinet, receipts and invoices scattered everywhere. Every day, she would call the bank, track the deposits, and make sure the numbers added up. It was a partnership, the same kind of partnership they had built over two decades together.

Young Glenn III, ten years old, worked the lot too. His father wanted him to learn the business, to develop the confidence to talk to customers, to name a price without flinching. But the boy hated it. The cold, the long hours, the rough environment – it wasn't fun for a fourth-grader. He was afraid that if he quoted too high a price, he would scare off the customer; if he quoted too low, his father would be disappointed. Glenn Sr. didn't actually care what number his son said – he just wanted the boy to try, to learn that boldness. But Glenn III didn't understand that. He dreaded those weeks on the lot.

Some of those weeks would haunt him for the rest of his life.

The trouble with Frankie started over watermelons, not Christmas trees.

Glenn had been expanding his operation at Hunts Point. He had started with twenty or thirty truckloads of melons per season, but he saw an opportunity to scale up. He made a deal with a larger competitor, a partnership that would let him handle over a hundred truckloads. It was a significant expansion, the kind of move that would establish him as a major player in the market.

Frankie didn't like it.

The expansion threatened Frankie's business. He had been operating at a certain level for years, and Glenn's growth would cut into his territory, his customers, his margins. They sold to the same buyers. Glenn's expansion would be a direct hit.

The friendship curdled. Frankie grew upset. Things got worse and worse. And Glenn, being Glenn, didn't back down. He had a way about him, Donna would say later. If you were mad at him, he would egg it on. He wouldn't give an inch. He would look at you and do something, say something, just to provoke a reaction. Nothing cruel, but relentless. Once Glenn decided you were an adversary, he didn't let up.

Frankie had connections. Everyone at Hunts Point knew that. He knew people who knew people, the kind of relationships that could make problems appear or disappear.

The market committee voted to strip Glenn of his marketing privileges. It was an extraordinary move, a punishment usually reserved for vendors who had violated the market's unwritten rules in serious ways. Glenn's offense, apparently, was competing too effectively.

Glenn sued them.

A small-town outsider, a market member from Florida, suing the mob-controlled produce market in the South Bronx. It was not a great position to be in. But Glenn was a lawyer, even if he didn't practice, and Donna was a lawyer, and they knew their rights. The market couldn't just strip his privileges because he was selling too many watermelons.

The lawsuit went nowhere, as far as anyone could tell. But it sent a message about what kind of man Glenn Walker was. He would not accept being pushed around. He would fight back through whatever channels were available to him.

And then came the Christmas trees.

The first time someone approached Glenn to collect protection money was in November 1992. Two men in long leather coats came into his Baychester lot and demanded $3,000 in cash. They politely explained how things worked and the benefits of cooperation. Glenn paid up.

The following year, however, Glenn hired three overnight security guards to protect his lot. He had decided that he didn't need any other protection. He had his own security. He paid his rent, he followed the rules, he ran a legitimate business. When the two men in leather jackets returned on Black Friday to collect their payment, Glenn declined.

Then the problems started.

His trucks were delayed at the market gates, held up for inspections that other vendors didn't seem to face. Shipments arrived late, or the paperwork was wrong, or there were questions about his permits. Workers he had hired for years suddenly quit without explanation. Tires on his trucks were slashed overnight. Tools disappeared from his warehouse. A delivery of pumpkins was rejected for reasons no one could explain.

Small things at first, annoyances more than threats. But the pattern was unmistakable. Other vendors didn't have these problems. Other vendors, the ones who paid, operated smoothly. Glenn's business was being squeezed, slowly and methodically, by forces he couldn't see and couldn't fight through normal channels.

He still wouldn't pay.

Then came the fire.

It happened in the middle of the night, December 1993. Someone doused his lot with a Molotov cocktail and lit a match. The flames consumed hundreds of trees, thousands of dollars of inventory, weeks of work. By the time the fire department arrived, there was nothing left but charred stumps and the acrid smell of burned pine.

Glenn stood in the ashes the next morning, surveying the damage. He knew who was responsible. Everyone knew. But knowing and proving were different things, and the people who had done this were careful.

He reopened the lot the next day. He cleaned up what he could, rushed to get replacement stock from his growers in Pennsylvania, and kept selling. When the television cameras showed up, he talked to them. He talked about his refusal to be intimidated. He talked about his determination to keep selling trees. He talked about what the holiday meant to the families who came to his lot every year. He played it up, Donna would say later, knowing exactly how to turn adversity into opportunity. American Journal, the TV newsmagazine, filmed a segment on his ordeal, portraying Glenn as a family man and principled businessman under siege by organized crime.

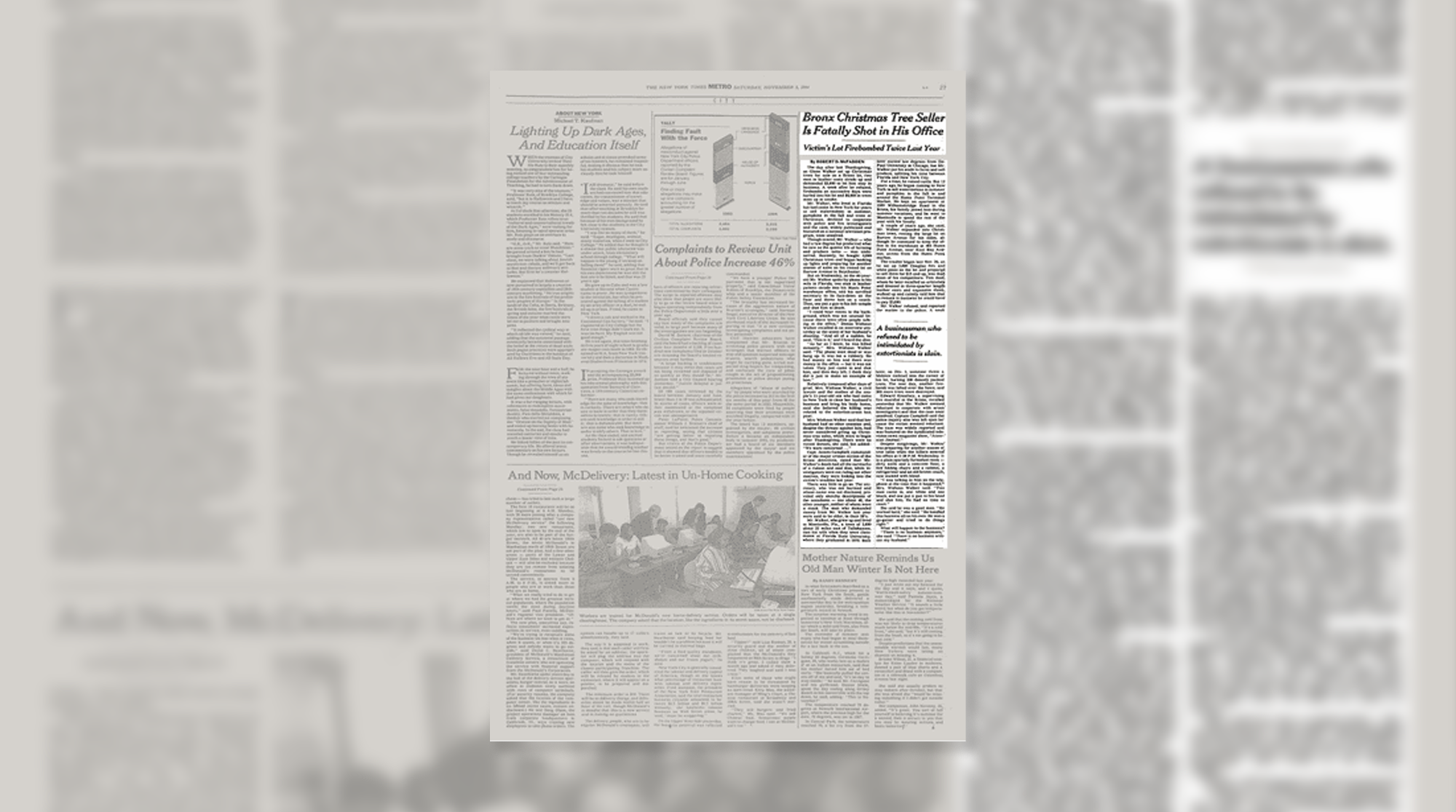

The story ran on the local news. It ran in the papers. Here was this nice family from Florida, just trying to make a living, being shaken down by the mob. All he wanted to do was sell his Christmas trees.

And then something extraordinary happened: customers came in droves.

They came from all over the city, from neighborhoods Glenn had never sold to before. They came from a hundred-mile radius, people who had read the articles and wanted to support the vendor who had stood up to whoever had burned his lot. They came because they admired his stubbornness, his refusal to back down. That year, despite the fire, despite the lost inventory, despite everything, Glenn Walker had one of his best seasons ever. He grossed more money than anybody had ever imagined you could make in one season on that lot.

The fire had been meant to destroy him. Instead, it had made him stronger.

But when Glenn went public with that story, something shifted.

He hadn't named names, hadn't pointed fingers at specific individuals. But the people who had tried to shake him down, the people who had firebombed his lot, understood what he had done. He had embarrassed them. He had made them look weak. He had turned their attack into a marketing opportunity, used their violence to generate sympathy and sales. And in their world, looking weak was unacceptable.

George Nash was another Christmas tree vendor, a man who had known Glenn and who operated a large wholesale business out of the Bay Plaza Shopping Center. Nash was a different kind of operator. He understood how things worked in the market. He had paid his tributes over the years, had kept his head down, had avoided the kind of confrontations that Glenn seemed to court.

After the firebombing, Nash heard the talk. His largest wholesale customer, a man with connections to the organization, told him flatly: Glenn Walker was a dead man.

"Mark my words," the man said. "Somebody's going to take him out."

Nash asked when.

"It's not going to happen anytime soon. But maybe like six or eight months down the road. When nobody's even thinking about it anymore."

Nash didn't know what to do with this information. He didn't know Glenn well enough to warn him, didn't know if Glenn would even listen. And besides, what could you say? Someone told me you're going to be killed, but not right away? Glenn already knew he had enemies. Glenn already knew he was taking risks. He had chosen to take them anyway.

The months passed. The Christmas season ended. Glenn went back to Florida for the winter, then returned to New York in the spring for watermelon season. He kept running his business, kept refusing to pay, kept being Glenn Walker.

October came. The leaves turned. The air grew cold. Glenn started preparing for another Christmas season on the lot.

Part Two

Glenn Walker's office at 405 Hunts Point Avenue was a small space in a low-slung warehouse building near the produce market. A desk, a phone, filing cabinets stuffed with paperwork. A frayed brown couch against one wall. Outside, the streets were narrow and industrial – one-story brick warehouses with metal roll-down gates, sparse streetlights, choked with eighteen-wheelers and refrigerated box trucks serving the meat and produce markets. The air smelled of diesel and rotting vegetables. Inside, Glenn handled the paperwork for his various operations: watermelons in summer, pumpkins in fall, Christmas trees in winter.

He had a secretary, a woman named Dirceline Delgado, who had worked for him for years. She handled the phones, managed the schedule, and kept the office running while Glenn was out on the lot or at the market. She was there on the afternoon of November 2, 1994.

It was a Wednesday. Three weeks before Thanksgiving. The pumpkin season had just ended, and Glenn was preparing for Christmas trees. He had spent the morning out at the Bartow Avenue lot, checking the fencing – which had been mysteriously tampered with by unknown antagonists that fall – and coordinating upcoming shipments from Pennsylvania. The first trucks would arrive soon. There were calls to make, arrangements to finalize.

Around midday, Glenn returned to the Hunts Point office. He settled behind his desk and picked up the phone to call Donna in Florida.

Outside, in the parking lot, a car sat idling. Two men inside, watching the building. They had been there since morning.

Workers at neighboring warehouses noticed the car but thought nothing of it. Cars came and went at Hunts Point. People waited for meetings, for deliveries, for business that was none of anyone else's concern. The two men had been sitting there for hours, patient, watching for Glenn to return from the lot.

At approximately 3:15 PM, the men got out of the car.

Glenn and Donna talked for thirty or forty minutes, the way they always did. It was an ordinary conversation, the kind married couples have when they're separated by distance but connected by decades of shared life. They talked about the business. They talked about their son, who was ten years old and doing well in school. They talked about Thanksgiving, which was coming up, and when Glenn would fly down to Florida to be with the family.

Donna remembered later that Glenn sounded relaxed. Normal. There was nothing in his voice that suggested anything was wrong, nothing that hinted at what was about to happen.

Then she heard something.

A commotion on the other end of the line. Voices she didn't recognize. The sound of the office door opening, or being forced open. And then a woman screaming. Dirceline.

"This is it," Glenn said.

The line went dead.

The two men who entered 405 Hunts Point Avenue walked past Dirceline Delgado, who screamed when she saw them, and into the back office where Glenn sat with the phone still in his hand.

One of them grabbed the secretary and held her down, pinning her so she couldn't run or interfere. The other went straight for Glenn. He grabbed him, threw him from his chair onto the frayed brown couch against the wall. Then he pressed the barrel of a gun to Glenn's left temple.

Donna, still on the phone a thousand miles away, heard shouting and then her husband's last words. She heard a single gunshot – a loud pop over the telephone line – and then silence.

Then the line went dead.

The bullet had entered Glenn's head at point-blank range. The medical examiner would later find multiple gunshot wounds – the shooter may have fired more than once to be sure. But that first shot, the one Donna heard, was fatal. Glenn Walker died instantly, on the floor of his office, three weeks before Christmas.

The killers left immediately. They walked out of the building, got into their car, and drove away. The whole thing had taken less than a minute. They didn't take the twenty thousand dollars in cash that Glenn kept in his desk for business. They didn't touch Dirceline. This wasn't a robbery.

This was a message.

Donna sat in her house in Florida, the phone still in her hand, trying to understand what had just happened. She called back. Busy. She called again. Busy. She kept calling, over and over, for what felt like hours but was probably only minutes. Maybe fifty times, she later recalled. Busy. Busy. Busy.

She didn't know what "this is it" meant. She didn't know if Glenn was hurt, or in danger, or already dead. She only knew that something terrible had happened, and she was a thousand miles away, and there was nothing she could do but keep dialing a number that no one would answer.

Eventually, she called the sheriff's office in Jefferson County. She knew the sheriff there. She asked him to get in touch with the police in New York to find out what had happened. He made the calls. But by then, the NYPD had already arrived at 405 Hunts Point Avenue. They had already found Glenn's body on the floor, face-up by the couch, bleeding from the head. They had already pronounced him dead at the scene. The time of death was approximately 3:16 PM.

That evening, a detective called Donna with the news she already knew in her heart.

She flew to New York the next day with Glenn III. The boy was ten years old. He had helped his father on the tree lot just months earlier, hating every minute of it, not understanding why his dad was so insistent that he learn the business. Now he would never understand. His father was gone.

The investigation began. Detectives from the 41st Precinct, one of the busiest in the city, took over the case. They canvassed the neighborhood, interviewed the workers who had seen the car idling in the parking lot all day. No one had written down the license plate. No one had gotten a good look at the men inside.

But they had Dirceline Delgado.

She was hysterical in the immediate aftermath, barely able to speak, barely able to form words. But she had seen the killers. She had been held down by one of them while the other shot her boss. In the days and weeks that followed, she worked with police sketch artists, trying to reconstruct the faces of the men who had burst into the office. It would take time. But eventually, she would identify one of them.

The break came seven months later, in June 1995.

A man named William Pinero was arrested on an unrelated charge. He was twenty-nine years old, with a criminal record and connections to the produce market at Hunts Point. During questioning, detectives noticed inconsistencies in his story. They pressed him. They showed him photographs, including a photo array that Dirceline Delgado had reviewed. She had picked him out. She had identified him as one of the men in the office that day.

Confronted with this evidence, Pinero decided to talk.

The confession came in pieces, extracted over hours of interrogation. Pinero admitted he was at the scene. He said he wasn't the shooter – that was his partner, a career criminal in his thirties named Michael Kealing – but he had been there. He had restrained the secretary while Kealing pulled the trigger.

And then he explained why.

Glenn Walker had been killed for defying an extortion racket. Pinero was part of a conspiracy to collect money from vendors for the right to sell Christmas trees on certain lots in the Bronx. Glenn had refused to pay. The price for the hit, Pinero said, was five thousand dollars.

"Do I get a deal?" Pinero asked the detectives more than once. "If I tell you everything, do I get a deal?"

The detectives made no promises.

Pinero named names – higher-ups who had planned the operation, provided the gun, arranged the whole thing. Some of those names led to dead ends. Some of the men were never found. The conspiracy extended beyond what the police could prove in court. But they had Pinero. They had his confession. They had Dirceline's identification.

Michael Kealing, the shooter, had fled to Philadelphia immediately after the murder. There, he shot and wounded a police officer during an unrelated incident and was arrested. Pennsylvania sentenced him to decades in prison. The Bronx prosecutors made a practical decision: extraditing Kealing for a murder trial would be costly and perhaps unnecessary, given he was already effectively locked away for life. They opted not to bring him back to New York.

So William Pinero became the sole defendant in the murder of Glenn Walker.

The trial took place in Bronx Supreme Court in mid-1997.

Donna testified. She took the stand and recounted the harrowing phone call – how she had been talking to her husband about ordinary things, about the business, about the holidays, and then heard the commotion, the scream, and those three words: "This is it." She described the gunshot, the silence, the frantic attempts to call back. She told the jury about the years of threats, the firebombing, the men in leather coats who had demanded three thousand dollars the day after Thanksgiving.

The defense tried to challenge her testimony, suggesting that her assumption of mob involvement was speculation. But Donna was a former prosecutor herself. She knew how to handle cross-examination. She stayed calm, stayed focused, told the truth as she knew it.

Dirceline Delgado testified too. She described being grabbed and held down, watching through the doorway as Kealing threw Glenn onto the couch and pressed the gun to his head. She identified Pinero as the man who had restrained her. The defense attacked her identification – arguing that seven months had passed, that the photo array might have been suggestive – but her testimony held up. The judge found the identification procedures sound.

And then George Nash took the stand.

Nash told the jury something extraordinary. Seven weeks after Glenn's murder, William Pinero had approached Nash on the Bartow Avenue lot. Nash had taken over the spot after Glenn's death. And Pinero had come to collect.

Ten thousand dollars, Pinero told Nash. For the big man. A soldier in John Gotti's crew.

Nash, terrified, paid up in two installments: $2,500 and $7,500. But he had done something clever: he had asked Pinero for a receipt.

And Pinero, incredibly, had written one.

On a scrap of paper, in his own handwriting, Pinero had documented the extortion payment after the first installment. He signed it "W.P." He had signed his own name to a receipt for mob tribute, weeks after committing murder to enforce that same system.

When Nash produced the receipt in court, the courtroom fell silent. The jury passed it among themselves, examining the handwriting, the signature, the damning words. This was not a random killing by a disturbed individual. This was a business transaction. This was a message sent to everyone in the industry about what happened to people who didn't pay.

The defense's theory – that Pinero was a lone actor, that the prosecution's mob narrative was speculation – collapsed under the weight of that piece of paper.

On August 9, 1997, the jury found William Pinero guilty of second-degree murder. He was sentenced to twenty-five years to life in prison.

Donna was in the courtroom when the verdict was read. She had waited nearly three years for this moment, had testified, had relived the worst day of her life in front of strangers. When she finally saw Pinero in person, she was shocked to realize she knew him.

"Real nice guy," she would say later, the words heavy with bitter irony. "He'd come around the market, that kind of thing."

The man who had helped kill her husband had once smiled at her and made small talk at Hunts Point. He had been friendly, personable, just another face in the world of the produce market. And then he had held down a screaming secretary while his partner shot Glenn Walker in the head.

Outside the courtroom, Donna told reporters she was pleased with the verdict but found little comfort in it. "There's no bringing Buddy back," she said, using her nickname for Glenn. And she expressed frustration that the men who had ordered the hit were not in the dock.

"Somebody told somebody who told somebody," she said. "Those people never answer for it."

The chain of command had held. But Donna had her own theory about where that chain began.

She had told the police, in the days after the murder, about Frankie. The man from Hunts Point who had been Glenn's friend and then his rival. The man whose business Glenn had threatened by expanding into watermelons. The man with connections – connections that went back decades, connections to people who could make problems appear or disappear. Donna believed that Frankie was at the root of Glenn's troubles, that the animosity that started over watermelons had metastasized into something lethal when Glenn refused to pay tribute on the Christmas tree lot.

She could never prove it. The police investigated, but nothing came of it. Frankie was never charged, never even named publicly as a suspect. The conspiracy, as far as the courts were concerned, began and ended with Pinero and Kealing and the shadowy "big man" that Pinero had mentioned.

But Donna still believes it. After all these years, she still believes that the man who smiled at her husband at the produce market, who worked alongside him in those early days, who turned bitter when Glenn's ambition threatened his business – she still believes he set the whole thing in motion. Some debts, in that world, were collected in ways that had nothing to do with invoices.

After the trial, George Nash tried to keep running the Bartow Avenue lot. But the murder had set off a cascade of trouble.

His largest wholesale customer, a man named Richie Longo, had seemed like a nice guy. Nash had been to his house on Long Island, had supper with his family, met his wife and kids. They did business together, buying and selling trees. Longo had connections, but Nash didn't ask too many questions. That was how you survived at Hunts Point.

After Glenn's death, Longo came to Nash with a proposition. The Bartow Avenue lot was available. "It's going to be either you and me doing it together," Longo said, "or me being your competitor. So what's it going to be?"

Nash partnered with him. He didn't have much choice. But his wife had warned him: don't get involved with this man. She was right. After all, Longo was the one who had convinced Nash to pay Pinero the $10,000 protection fee.

It was only later that Nash learned who Richie Longo really was. A soldier for John Gotti. A made member of the Gambino family. He had a prior conviction for possession of a submachine gun. All those dinners, all that friendliness, had been a front. Nash had been doing business with the mob without fully understanding it.

The partnership went bad almost immediately. Nash got robbed at gunpoint on the lot, losing nearly an entire year's income in cash. He came to believe the robbery had been set up by people close to Longo, who would have known when money was on the premises. Then Longo disappeared, owing Nash fifty thousand dollars and a whole truckload of trees that never materialized. The whole thing caused Nash endless trouble, and it took him years to recover.

The next season, Nash came back armed. He hired private security, men with guns. He had an armed bodyguard with him every second. His workers from Vermont were all packing. Every time a car rolled slowly into the lot, everybody went on full combat mode.

At the end of that season, Nash looked at his crew, and they looked at him, and someone said: "This is Christmas. What are we doing?"

Nash got out of the Bronx entirely. He abandoned the wholesale business, went back to Manhattan, where the lots were smaller and the money was thinner but nobody was getting murdered. He never went back to Bartow Avenue.

The murder of Glenn Walker became a turning point.

Federal prosecutors had been building cases against organized crime at Hunts Point for years, but Glenn's death – widely publicized, impossible to ignore – added urgency to their efforts. Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who had made his name as a mob-busting prosecutor, pushed for reforms. The city established a Business Integrity Commission that required background checks for market vendors, effectively freezing out those with criminal records or mob ties. Federal RICO cases took down key figures in the Gambino and Genovese families.

Angelo Prisco, the Genovese capo who had controlled much of the Bronx rackets, was convicted in 1998 on federal extortion charges. He was convicted again in 2009 for racketeering and murder and sentenced to life in prison. Whether he had any direct involvement in what happened to Glenn Walker was never established in court. The old systems crumbled.

Within a few years, the Christmas tree tribute system that Joseph "Piney" Armone had established in the 1930s was effectively dead. New vendors entered the business who had never heard of Armone, who had never paid protection money, who competed on price and quality and location without worrying about men in leather coats showing up to collect. The mob, as George Nash would later put it, had smelled money in the Christmas tree business for a while, but then it wasn't worth the trouble anymore. Too much heat after the Walker case.

Donna Walker stayed in Florida and raised her son. She practiced law, the profession she and Glenn had trained for together at DePaul all those years ago. She never remarried.

"Glenn was the love of my life," she would say.

She thought often about what those last words meant. "This is it." She believed Glenn had known, in that moment, that he was going to die. That he had seen the men approaching through the window of his office, had understood what was about to happen, and had wanted to tell her something before it was over.

She thought, too, about whether Glenn could have done anything differently. Whether he could have paid the money and saved his life. Whether his stubbornness had been courage or foolishness or some combination of both.

"He thought they might rough him up," she said. "Beat him up or something. I don't think he thought they would kill him."

And if they had just beaten him up?

"He would have been there in a wheelchair," Donna said. "However he had to get there. He would have been at that lot, and he would have had the media there, and he would have had another great year."

That was Glenn Walker. Stubborn to the end. Principled to the end. Absolutely certain that he was right.

Glenn Walker III grew up to be a man who never talked about what happened.

He joined the Air Force after high school and served for nearly twenty years, rising through the ranks, building a career far from the produce markets of the Bronx. He got married. He had children. He made a life for himself on his own terms. In a way, he took the Walker stubbornness in a different direction – instead of fighting the mob in business, he fought for his country in uniform.

But he carries scars.

When families across America put up their Christmas trees, Glenn III does not. There is no tree in his house. The sight and smell of fresh-cut pine bring back too many memories: the cold of the lot, the fear of disappointing his father, and then the loss that came after. He was ten years old when his father was killed. He is in his forties now, and he still cannot bring himself to celebrate the holiday the way other families do.

His mother respects his silence. On the rare occasions he speaks of his father, it is with pride. Glenn Jr. was brave, principled, unwilling to bend. But Glenn III also understands, in a way his father perhaps never did, the cost of that stubbornness. He paid part of that cost himself. He has been paying it ever since.

The lot on Bartow Avenue still sells Christmas trees.

Every December, families from Co-op City and Bay Plaza drive over, browse the rows of Fraser firs and Scotch pines, and pick out their trees the way they have for decades. The vendor now is a man called Crazy Al – Alfred Diallo, an independent operator with no mob connections, no tribute to pay, no fear of firebombs or gunmen. He sells his trees, collects his money, and goes home at night without an armed guard.

Most of his customers have no idea that the ground they're standing on was once the center of a war. They don't know about Glenn Walker, the stubborn farmer from Florida who refused to pay protection money. They don't know about the firebombing, the murder, the trial. They just want a nice tree for their living room.

But the freedom they have – the freedom to buy a Christmas tree from an honest vendor at an honest price, without that price including a hidden mob tax – exists in part because of what Glenn Walker did. He refused to participate in a corrupt system. He paid the ultimate price for that refusal. And in the aftermath, the system itself was dismantled.

George Nash eventually passed the family business down to his daughter, Ciree, who runs Uptown Trees in Manhattan now. The "five families of Christmas" still exist in a sense – a handful of dynasties competing for the best corners – but their battles are fought in permit applications and marketing now, not on street corners with guns. A documentary called "The Merchants of Joy," released in 2025, follows several of these tree-selling families through a season. The trailer mentions that they "battle the Mafia" – but these days, that's history, not present tense.

Every December, the trees go up across New York City. The lights come on. The smell of pine fills apartments from the Bronx to Brooklyn. Somewhere in Florida, Donna Walker watches the season arrive and thinks of her husband, the love of her life, who believed so fiercely in doing things the right way that he died for it.

This is it.

The End